Chapter IV: The Cakewalk Wars

Section 1 - Poetry

Section 2 - Images

Section 3 - Music

Golliwogg's Cakewalk may now be the most celebrated remnant of the cakewalk, but in the early 20th century when it was written, it was just the tip of the iceberg. Baudelaire died before that craze hit, but the following two poems make only too clear the link between dance and illness that added to the French fascination with the whole cohort of frenzied dances that appeared in the same time frame.

Selections from Fleurs du mal

By Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867)

| Danse macabre | The dance of death |

|

Fière, autant qu'un vivant, de sa noble stature Vit-on jamais au bal une taille plus mince? La ruche qui se joue au bord des clavicules, Ses yeux profonds sont faits de vide et de ténèbres, Aucuns t'appelleront une caricature, Viens-tu troubler, avec ta puissante grimace, Au chant des violons, aux flammes des bougies, Inépuisable puits de sottise et de fautes! Pour dire vrai, je crains que ta coquetterie Le gouffre de tes yeux, plein d'horribles pensées, Pourtant, qui n'a serré dans ses bras un squelette, Bayadère sans nez, irrésistible gouge, Antinoüs flétris, dandys à face glabre, Des quais froids de la Seine aux bords brûlants du Gange, En tout climat, sous tout soleil, la Mort t'admire |

Carrying bouquet, and handkerchief, and gloves, Was slimmer waist e'er in a ball-room wooed? The swarms that hum about her collar-bones Are made of shade and void; with flowery sprays Who laugh and name you a Caricature, Come you to trouble with your potent sneer Or do you hope, when sing the violins, Fathomless well of fault and foolishness! And truth to tell, I fear lest you should find, Your eyes' black gulf, where awful broodings stir, For he who has not folded in his arms O irresistible, with fleshless face, Withered Antinoils, dandies with plump faces, From Seine's cold quays to Ganges' burning stream, In every clime and under every sun, |

English translation reprinted from Baudelaire, his prose and poetry, ed. by T. R. Smith, 1919.

The dancing serpent

Le Serpent qui danse

Que j'aime voir, chère indolente,

De ton corps si beau,

Comme une étoffe vacillante,

Miroiter la peau!

Sur ta chevelure profonde

Aux âcres parfums,

Mer odorante et vagabonde

Aux flots bleus et bruns,

Comme un navire qui s'éveille

Au vent du matin,

Mon âme rêveuse appareille

Pour un ciel lointain.

Tes yeux, où rien ne se révèle

De doux ni d'amer,

Sont deux bijoux froids où se mêle

L'or avec le fer.

À te voir marcher en cadence,

Belle d'abandon,

On dirait un serpent qui danse

Au bout d'un bâton.

Sous le fardeau de ta paresse

Ta tête d'enfant

Se balance avec la mollesse

D'un jeune éléphant,

Et ton corps se penche et s'allonge

Comme un fin vaisseau

Qui roule bord sur bord et plonge

Ses vergues dans l'eau.

Comme un flot grossi par la fonte

Des glaciers grondants,

Quand l'eau de ta bouche remonte

Au bord de tes dents,

Je crois boire un vin de Bohême,

Amer et vainqueur,

Un ciel liquide qui parsème

D'étoiles mon coeur!

Images

Find below all manner of images conveying the role the cakewalk played in turn-of-the century Paris.

First, though, a more traditional scene. By contrast with cakewalk mayhem, it's obvious that a ballet class telegraphs order and authority.

The Dance Class (c. 1874), Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

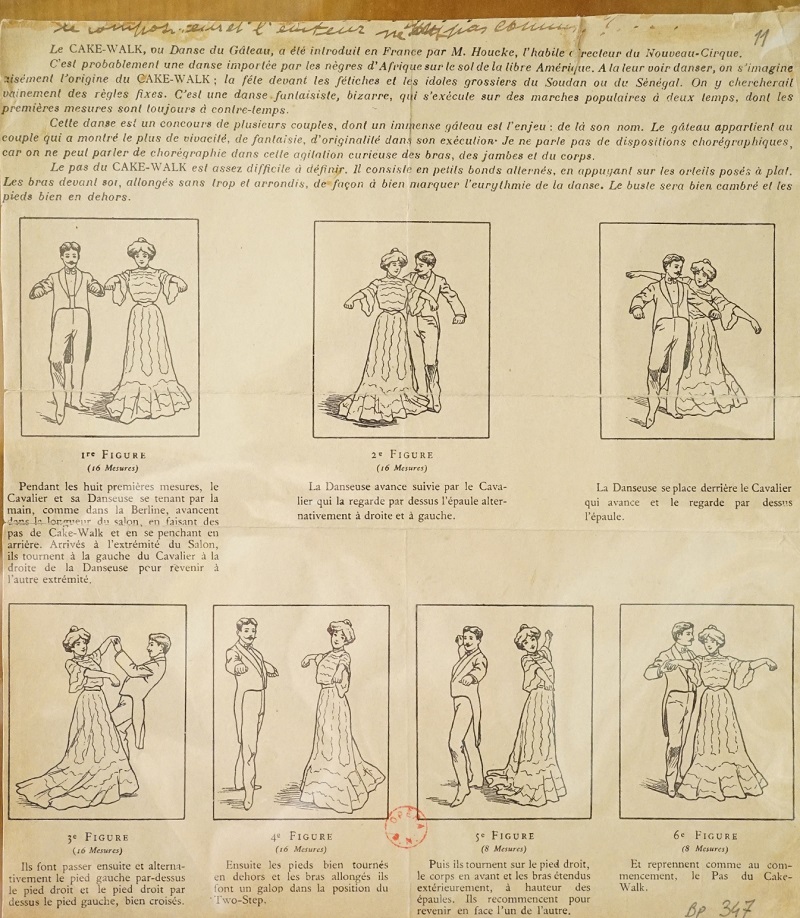

Here a proper dance school attempts to convey the intricacies of the cake walk steps while lamenting its bizarre nature and fantastical turns.

The following image graphically conveys the courteous"danse d'autrefois" vis-a-vis the menacing "danse d'autour d'hui."

And below we see that menace played out in a traditional ballet pose; it becomes clear that the menace, in large part, resides in the race of the creators, rather than the particular steps, of the cakewalk. this cartoon facetiously proposes a “white slave trade,” clearly a thought so inconceivable as to appear farcical. The image implies a rape scene in the guise of dance, with the muscular black male carrying away his nude, ravaged victim.

While the Elks, the American couple who brought the cakewalk to France, were white, all their sidekicks were black.

Moving away from both ballet and whites, one begins to see the cakewalk portrayed in its "natural" primitivist setting. Here, in a carnival scene from the “Pays- Noir” or “Nation of Blacks,” a black disguised as a white turns on her compatriots and insults them, demanding in rude language that the “worthless bits of coal” “shut up.”

Not only primitive, but the very epitome of laughable incompetence, these babies levitate in lieu of nursing:

“Les petits imprudents, au lieu de téter, ils ont soufflé." (The little foolhardy ones; instead of sucking, they puffed.)

Sex was never far from the equation.

"You know, your wife has betrayed you with a negro!"

"Oh! Cool!... I’ll have cakewalk lessons at my fingertips!"

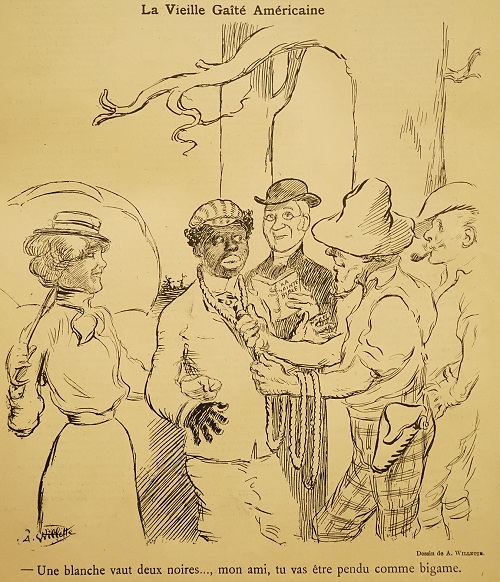

The unfortunate black man below, who'd apparently taken up with a white woman, is condemned as a bigamist since his white conquest counts for two.

Top caption: "The old American good-cheer"

Bottom caption: "One white is worth two blacks—my friend, you are going to be hung as a bigamist."

The black man pictured here gallantly proffers a white arm, probably recently acquired in some violent escapade, to a naked woman who further emphasizes his uncultivated tendencies.

“Will you permit me to offer an arm?”

The splendid portal to the cathedral at Conques,France, dating from the 1100's, illustrates well the long-standing equation of monkeys, sin, and damnation. Similar equations were at work in fin-de siècle Paris, and they often included the cakewalk.

Tympan de Conques

The publication of Darwin's Origin of Species in 1859 coincided with the French forays into Africa, and monkeys were very much on people's minds. It was very convenient to assume that evolutionary stages had passed from African monkeys through African blacks before reaching the exalted heights of the French themselves, and hundreds of cartoons from the era feature cakewalkers, usually black, in the company of monkeys. Clearly an Africa viewed as primitive, barbaric, and alluring was never far from the minds of the French as they viewed this novel dance.

This announces the arrival of a troupe of exotic dancers at the Nouveau-Cirque, a popular circus/music hall in Paris. The circus, music, and dance all joined as popular entertainment.

Not only monkeys but primeval reptiles seem to have given rise to the ever-fascinating and forbidden dance.

In the famous poster below the queen of the cafe-concert, Jane Avril, demonstrates graphically the risqué possibilities of contemporary dance. It soon becomes clear that whites too are happy to join in the sinful pleasures.

“Jane Avril” (1893) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, Albi 1864–1901 Saint-André-du-Bois), via The Metropolitan Museum of Art is licensed under CC0 1.0

In a nice inversion, a black here comments that because good whites have taken the cake-walk from poor negros, the poor negros will take waltzes and minuets from the good whites.

All manner of eminent statesmen were portrayed in various cartoons as forsaking those waltzes and minuets and joining the general dancing mayhem that had Paris in its grip.

Here, in a French version of black dialect, “Mousié [Monsieur] Roosevelt” [Theodore Roosevelt, who was President of the US from 1901-1909] is laughingly quoted as saying there’s no difference between whites and blacks.

Hah!” is essentially the verdict. “that would be too nice...”

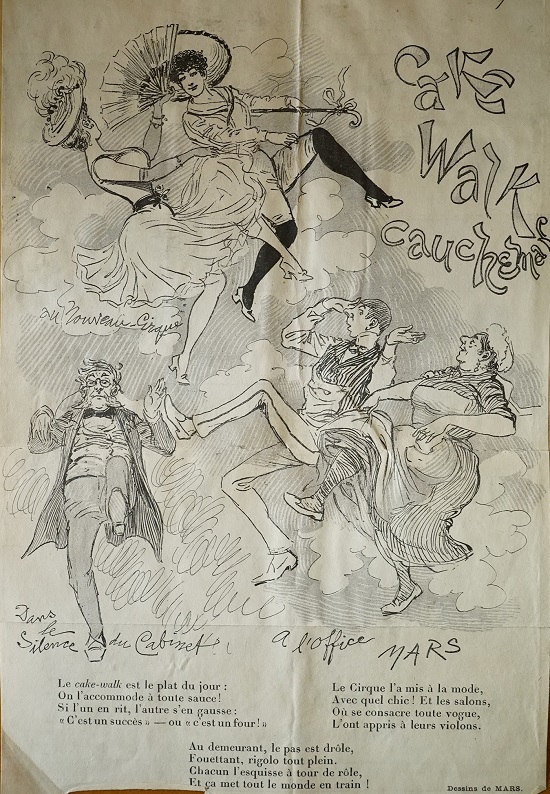

This cakewalk "cauchemar" or "nightmare" is obviously a lot of fun!

This article from the July 14, 1901 issue of Le Courrier français expands on the lazy nature of the nègre, who, it claims, prefers to spend life laying in the sun when not busy satisfying his cannibalistic tendencies by devouring whites.

Not only the music itself, but the decorative flourishes surrounding it make clear that EVERYONE can dance the cakewalk.

As this shot of Judy Garland in the 1938 film, ”Everybody Sing,” demonstrates, blackface, the practice of applying cork to a white face, lingered on the entertainment horizon well into the 20th century. The practice went back centuries (witness Othello), but reached its apex with the popularity of white minstrel shows in the late nineteenth and early 20th centuries.

In this shocking and all-too-recent 2013 Facebook posting, Anne Leclere, National Front politician, compared Christiane Taubira, French Minister of Justice, to a monkey and posited that she’d be better off swinging from trees than serving in government. One hundred years have passed since the cakewalk craze, but it's clear that whites still parade their racism by placing blacks in the jungle.

Musical examples

Golliwog's Cake Walk from Children's Corner Suite, 1906-1908 (Walter Gieseking)

Second only to "Clair de Lune," this may be Debussy's most famous contribution to the piano literature, though far from his most ambitious! Despite the unpleasant associations of the cakewalk with minstrel shows, blackface, and the rampant racism of the era, the charm of the music's cakewalk rhythms and its swaggering joviality have endeared it to listeners and performers alike. The middle interlude, with its apparent snide reference to Wagner's Tristan und Isolde only heightens the pleasure we take here in less portentous pastimes.

"General Lavine" - excentric, Prelude no. 6, Book 2, 1912-1913 (Kautsky, 2014)

(Note: this and other links to the Preludes require a free Spotify account)

General Lavine, the American clown, is instructed by Debussy to saunter to a cakewalk rhythm, and the hidden reference to "Camptown Races" in the middle section, seals his fate as part of a minstrel show. Circuses, minstrel shows, and cabarets were all part of the entertainment scene in fin-de-siècle Paris, and one of Debussy's charms is his ability to incorporate elements of all three into his "high" art.

Le Petit Nègre, 1909 (Gieseking)

This is Debussy's other cakewalk-- less celebrated than Golliwogg, but just as directly appealing. Its title tells us exactly what the racial stereotypes were for the dance.

Danse (Tarentelle styrienne), 1890 (Gieseking, 1953)

This piece has had a number of incarnations. It was first written by Debussy in 1891 and published as Tarantella styrienne; he revised it slightly and re-published it in 1903, titling it Danse. Later yet, in 1923, Ravel orchestrated it, no doubt attracted by the sizzling rhythms and energy of Debussy's creation. Tarantella rhythms, with their 6/8 meter, and propulsive drive, have attracted composers as unlike as Schubert, Liszt, and Rachmaninoff across the centuries.